Between 1963 and 1979 Kenya was faced with a

serious armed conflict with the people of Somali origin living in

the North Eastern province. The focus of the conflict was secession

to Somalia. With the support of Somali government, the ideology

spread into NFD, a Somali predominant region in Kenya, The Somalis

in Ogaden and the Haud in Ethiopia initiated the whole campaign by

forming an irredentist movement during the pre-colonial era. The

primary purpose for this movement was to fight for a unified

Somalia comprising of all the Somali speaking people in the Horn of

Africa.

British colonialists attempted to resolve the matter by

appointing an independent Commission of Inquiry to carry out a

referendum exercise to verify the desire of the Somali community in

the Northern Frontier District. Although the Commission established

that the interest of the Somali people was to secede, the Kenyatta

government refused to allow them to secede. Consequently, an armed

insurrection erupted. In response, the Kenyan government deployed

troops to counter the secessionist irredentists liberators.

Having fought a successful and an intense battle with the

Somali irredentist, the original problem remains unsettled. The

Somali government has not renounced their claim on the Kenyas' NFD.

The secession ideology is still unresolved to date.

Recommendation: The Kenya government and the Somalia

Government should be made to resolve the issue by first and

foremost, Somalia renouncing her territorial claims of NFD, and by

signing a treaty in the United Nations ratifying the agreement.

Both nations should pledge to honor the existing boundaries and to

live in peace. These resolutions must be endorsed and ratified by

the Organization Of African Unity.

OUTLINE

Thesis: Although Kenya battled the pro-Somali insurgent

irredentists who fought to liberate the Northern Frontier District

and annex it to Somalia, the predicament is still unresolved. For

the insurgency to be defeated, a multifaceted approach was needed:

adaptation in the Kenyan Army's tactics, favorable operational

approach in the Kenya's political and economic handling of the NFD,

while the reduction in outside support (by Somalia) also helped. A

coordinated military, political, and psychological campaign was

necessary to counter the insurgency. For the last decade peace has

continued to prevail in the region despite the continued deployment

of troops in the Northern Frontier Province. The matter requires a

lasting solution to avoid any future military confrontations.

FOREWORD

This paper does not try to pre-empt war between Kenya and

Somalia. It does not either prophecy or conjecture a possible

reaction between the two nations. The doctrine, machinations,

and the conflict discussed in this paper are based on real

situations and people. Many may find shortcomings in some of

the phrases or actions decided during the skirmishes. However,

this bears a true reflection of events that took place in the

conflict.

The center of focus is the dispute and the campaign

activity which began soon after Kenya attained her

independence. The scenario and units mentioned are in

consonance with actual occurrence. Finally, I wish to

apologize for any references which may appear humiliating and

sometimes annoying to a cross section of people who either

participated in the campaign or merely sympathized with the

situation.

This paper basically analyses and illustrates what

transpired, the reasons why, the cause, and the lessons

learned by the Kenya Defence Forces. The socio-political

premises were given alot of emphasis in this paper since they

provided for a primary platform for this conflict.

The final conclusion focuses on the overriding

circumstances under which such issues are common in the

continent of Africa and in particular, in the Horn of Africa.

It ends with a recommendation on the Kenya-Somalia dispute, a

dispute which dates back to the pre-independence era.

INTRODUCTION

Following Kenya's independence from British colonial

rule on 12th December, 1963, the country faced a serious

armed conflict with the Somali community in the Northern Frontier

District which was getting support from the government of

neighboring Somalia. The estimated Somali community of 250,000, who

had migrated into the region between 1894 and 1912 was fighting to

secede from Kenya to form part of greater Somalia.

Throughout the period between 1963 and 1967 there were serious

armed skirmishes which translated into massive loss of life on both

sides. The Kenya government suffered serious set backs due to the

lack of local support and adequate intelligence network. Another

drawback was the encountering of a two-pronged attack by the

Somalis in Ogaden, Ethiopia, and those from Somalia who had formed

a strong irredentists force to fight for an homogeneous Somali

community.

Over the period, the central government of Somalia offered the

irredentist moral and material support in both North Eastern Kenya

and South Eastern Ethiopia. Further external support was received

from some former colonialists and Arab sympathizers.

Following these developments, Kenya government contemplated

introducing military forces in the Northern Frontier District to

combat the envisioned protracted guerrilla campaign by the Somali

irredentist. In June, 1963, military posts were established in the

towns of Mandera, Garissa, and Wajir. Outposts were subsequently

also organized at Buna, Gurar, Moyale, and Malka-Mari. To date,

military detachments and outposts are still in these towns to

ensure that peace prevails in the region.

THE COUNTRY AND THE PEOPLE OF SOMALI ORIGIN

Somalia is a nation which embraces an homogeneous society

with one religion, one common cultural heritage, and one language.

The Somali people were founded from two cousins of the prophet

Mohamed: Samaale and Sab. The family of Samaale became nomads while

the family of Sab became settled farmers. The Somalis have a very

strong background of family clanism segmented further into lineages

which form their basic dialectical identity. The Somali-speaking

people are divided into six clan families comprising 75% of the

Somalis coming from the offsprings of Samaale. These are the Darod,

Hawiye, Isaaq, and Dir. The offsprings of Sab are the Digil and

Rahanweyn which form the other 20% of the Somalis. The remaining 5%

are the non-Somali speaking people. The Somali speaking people

inhabit three nations within the Horn of Africa: Djibouti, North

Eastern Kenya, and South Eastern Ethiopia (Haud/Ogaden).

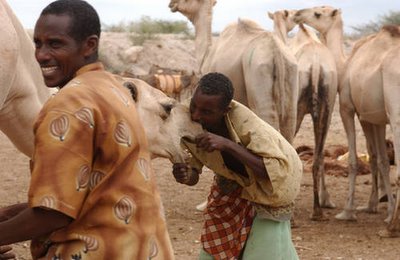

Click here to view image

Somalia was founded by a unification of two pre-colonial

territories: the former British Somaliland in the North and the

former Italian Somaliland in the South. Both attained independence

almost at the same time on July 1st, 1960. That same year, the two

formed a merger to create what is currently known as the Somali

Republic, which later changed to the Somali Democratic Republic.

However, the immediate post-independent era witnessed internal

socio-political instability centered on two main issues: the

amalgamation of the two former colonial territories and the support

of the irredentist conflict activities in North Eastern Kenya and

South Eastern Ethiopia.

POLITICAL OVERVIEW

After an excruciating political campaign between the

political aspirants from former British Somalia and the former

Italian Somalia in July 1960, Mr Aden Abdulla Osman

became the first president and Dr Abdirashid Ali Shermarke

became the first prime minister. During the next general

elections of 1964, Mr Abdirazak Haji Hussein became the second

Prime Minister while Mr Aden Abdulla Osman continued to be the

president. Mr A.H Hussein was considered by his contemporary

political opponent, Dr Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, as favouring

Ethiopian and Kenyas' legitimate sovereignty over Somali occupied

areas. Despite many internal rivalries, President Aden Abdulla

Osman appointed Mr Hussein the Prime Minister and he remained in

office until the 1967 general elections.

The general election of 1967 changed the political line.

Mr Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was elected the president and Mr

Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal became the Prime Minister. Mr Egal was a

moderate personality while believing in Pan-Somalism, desired to

improve relations with other surrounding African countries. He

preferred directing the nations energies to combating socio-

economic evils instead of confrontations with neighboring

countries. Although he favoured good relationship with Kenya and

Ethhiopia, he did not acknowledge Somalia's territorial claims. He

however, created an atmosphere where the matters could be

negotiated peacefully. This notwithstanding, Prime Minister Mohamed

Egal's administration was seen by his opponents as a corrupt regime

riddled with complex nepotism. Eventually, Somali political

intellectuals and members of the Armed forces became greatly

disgruntled with the trend of Egal's administration.

During the early stages of Somalia's independence,

the military were deliberately denied political participation.

Military pre-occupation with the Kenya-Ethiopian border activities

contributed to preventing military involvement in politics.

However, the military were increasingly dissatisfied with the

deteriorating situation, particularly the lack of progress in

solving the Pan-Somali issue. On the October 15th, 1969, hardly two

years after the general election, Dr Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was

assassinated by his personal body guard over his alleged

mistreatment of the assailants' small relatives.

However, it was perceived by the world community as a covert scheme

by the military to pave way for a premeditated coup

attempt, motivated by their dissatisfaction with the government.

Coincidentally, Mr Mohammed Egal was out of the country when the

President was assassinated. On his return, he arranged for the

selection of another candidate for the Presidency, a member from

the Darod clan-family. Mr Egal was from the Isaaq clan while the

Late president was from the Darod clan, therefore, the replacement

was by a fellow clansman of the slain president.

Once again, this selection displeased a portion of the Armed

Forces and civilian critics, who desired a more radical leader.

Consequently, during the morning of October 21st, 1969, Army units

took positions in Mogadishu and rounded up all senior political

leaders and other influential individuals. The Police had no

option, but to reluctantly collaborate with the Army. The civilian

government was immediately toppled, replaced with the Supreme

Revolutionary Council (SRC), and Major General Mohammed Siad Barre,

commander of the Somalia National Army was immediately installed as

its President.

The fundamental goals of the new military junta were: to

end tribalism, nepotism, corruption, and misrule; the honoring of

existing treaties, and full support of the national liberation

movements seeking Somali unification. Henceforth, the name of the

Somali Republic was changed to the Somali Democratic Republic (SDR).

Observers believed that the Soviet Union, who was then a very close

ally of Somalia, had masterminded the coup in order to enhance her

regional strategic interests in the area.

THE DISPUTE

The Kenya-Somalia dispute has not been about land, but rather

about unification of all Somalis within Somali Republic and the

neighboring countries. The present disputed frontier, the Northern

Frontier District, (Ref: Map-5 & 6) was an historical accident

dating back to Britain's treaty with Italy which partitioned the

Sudan and East Africa from Ethiopia and placed the Somalia plateau

into British and Italian zones of influence for administrative

purposes.

In 1909, the Somalis' Westward migration had reached the Tana

River and had driven the Boran Galla out of Wajir, as well as many

other small tribes in the area. In 1912, Wajir was occupied by the

British constabulary, but had to be hastily evacuated four years

later after 80 people were killed in a surprise attack by Somalis

against Lt Elliot's constabulary at Serenli in the upper Juba.

However, the Northern Frontier District came under effective

British administration for the first time when Moyale and Wajir

were garrisoned by regular British troops in 1919.

The Somalis' westward movement was interrupted by

the British colonial administration between 1895 and 1912. In 1920

Lord Milner concluded a convention to Italy handing over the strip

on the Juba which by then formed part of Kenyan territory. (Ref Map

5). According to Lord Milner's opinion, it was administratively

uneconomical to retain the Juba section. However, prior to

implementation, there was a legal requirement for the British

Parliament to ratify the treaty allowing the Jubaland region to

become part of the Italian colony. However, it was not until the

29th of June, 1925 when the treaty was finally ratified. Kenya

still claims that Britain was morally wrong to have ceded Jubaland.

Perhaps this is why the British did not want to support again the

Somali campaign demanding the secession of NFD to Somalia, since

this move could have created tension. The British justified their

handing over of Jubaland to Italian colonialist by maintaining that

this was the only way to keep Somalia together as a single society

and to allow Somalis full utilization of their traditional grazing

lands.

The emergence of the dispute between Kenya and Somalia was

further triggered by the achievement of independence by both

countries. This came about when the Somali community in Kenya

publicly opted to become part of the Somalia Republic. One of the

first Prime Ministers of Somalia, Dr Abdirashid Ali Shermarke once

made a sentimental statement about the dispute:

"Our misfortunes do not stem from the

unproductiveness of the soil, nor from a lack of

mineral wealth. These limitations on our material well-

being were accepted and compensated for by our

forefathers from whom we inherited, among other thing,

a spiritual and cultural prosperity of inestimable

value:

the teaching of Islam on the one hand and lyric

poetry on the other. . . .NO! Our misfortune is that our

neighboring countries, with whom like the rest of

Africa, we seek to promote constructive and harmonious

relations, are not our neighbors. Our neighbors are our

Somali kinsmen whose citizenship has been falsified by

indiscriminate boundary "arrangements". They have to

move across artificial frontiers to their pasture

lands. They occupy the same terrain and pursue the same

pastoral economy as ourselves. We speak the same

language. We share the same creed, the same culture,

and the same traditions. How can we regard our brothers

as foreigners?"

GREATER SOMALIA PHENOMENA

The greater Somali phenomena emerged in the year 1956,

when the Somali Trust Territory moved closer to possible

unification. This move alarmed Ethiopia which feared the emergence

of greater Somali authoritative influence in the Horn of Africa.

Meanwhile, the British government expressed no objection to the

two Somali territories uniting to form one nation. In response, the

Ethiopian regime expressed its dissent and stepped up anti-British

propaganda campaign in the press and over the radio. The central

focus of concern for Ethiopia was the Somali settlements within

their territory, Ogaden and the Haud, and the possibility of

forfeiting all the territory occupied and used for grazing by the

Somalis.

By that time, the greater Somali idea had begun to

attract international interest. The United States supported the

British position. This encouraged the Ethiopian Emperor to seek

support from the Soviet Union. The greater Somalia concept had

Click here to view image

developed deep roots and later in July, 1960 the two Somalia

territories were united into one Republic. To thwart any

speculations by the Ethiopian regime, the British clarified her

position regarding the greater Somalia phenomena by reiterating

that it was not going to support any claim affecting the integrity

of French Somaliland, North Eastern Kenya or Ogaden and the

Haud in Ethiopia. Any existing dispute was to be left to the parties

concerned to resolve.

When Jubaland was transferred to Italian Somaliland in

1925, North Eastern Kenya remained as a province of Kenya.

It stretched from Lake Turkana (Rudolf) down to the South of

Kolbio (Ref: Map 5). Within the then NFD were six districts

Mandera, Wajir, Garissa, Isiolo, Marsabit, and sub-district of

Moyale. Presently, the two districts of Marsabit and Isiolo are in

the Eastern Province while the rest of the districts are in the

North Eastern Province. Although the two districts of Marsabit and

Isiolo were predominantly occupied by the Boran-Galla tribes, there

were small percentages of Somali immigrants in the area.

Until 1963, when Kenya attained her independence, the North

Eastern region had been isolated from the rest of Kenya by the

British colonialist laws passed in 1902 and in 1934 which

restricted the movement of all persons entering or leaving the

district. Following the achievement of independence by both Kenya

and Somalia, Kenya found it appropriate to encourage participation

in the political arena by the Kenyan Somalis. As a result,

political parties were formed such as the North Eastern Peoples

Progressive Party (NPPP) and others.

The political parties campaigned vigorously for secession,

instead of joining hands with pro-Kenyan independence

parties such as Kenya African National Union (KANU) and Kenya

African Democratic Union (KADU). Following the continuing political

pro-secessionist campaign, Britain found it necessary to establish

an independent Commission to carry out a form of referendum to

verify the desire of the people of the North Eastern region. The

Commission composed of Mr G C M Onyiuke of Nigeria and Major

General M P Borget, CBE, DSO, CD, of Canada started work on the

22nd of October, 1962. Meanwhile, pro-secessionist political party

campaigning was picking up. A three point memorandum was prepared

for the Commission with the following points: one, secession from

Kenya forthwith; two, establishment of a legislative assembly, and

three, independence and re-unification with the Somali Republic by

an act of union.

The commission was faced with two fundamental opinions from

the Somali community in NFD, representing those who wanted to

remain part of Kenya and those who were in favour of secession and

the subsequent re-unification of NFD with the Somali Republic.

Among the people of NFD were three distinct racial groups with

conflicting opinions: the Somalis were who in favour of secession,

the riverine tribes who favoured to be part and parcel of Kenya,

and the Galla (Oromo) people who had mixed opinions. However, Wajir

and Mandera, which were predominantly Somali occupied areas, were

unanimously in favour of secession and union with Somalia. The

Somalis at Moyale, Isiolo, and Marsabit, together with Muslim

Boran, were also in favour of the union with Somalia.

The non-Somali speaking people of the North, namely: the

Rendille and the El Molo were in favour of secession while the non-

Muslim Boran and Gabbra were against secession. Their preference

was to remain part of Kenya. Incidentally, people from Moyale

township, Isiolo township, and a small element of people from

Garissa township had mixed feelings about seceding to Somalia.

Following its investigation, the Commission concluded that the

majority of the people of NFD favoured secession. This was based on

the overall wishes of the predominant Somali-occupied districts of

Mandera, Wajir, and Garissa. At this juncture, the most intriguing

point noted by the Commissioners was that those Somalis wishing to

secede required a limited, but continuous British rule while they

prepared their own government in order to join Somalia as an

established government body.

The new dimension of "forming a government body" was

precipitated by the fact that both Kenya and Somalia had attained

Self government as a step toward independence during the referendum

period. It was further exacerbated by the emergence of political

parties in the region which appeared to enjoy a competitive

atmosphere with other emerging parties.

Finally, the Commission resolved that five out of

six districts favoured the secession by a majority vote.

These were Garissa, Wajir, Mandera, Moyale, and Isiolo. The

percentage in favour was calculated at well over 80% of the total

population in the NFD.

DEFENCE PACT WITH ETHIOPIA

Having realized the expansionist ideological development

of the Somalis in the region, Kenya and Ethiopia signed

a Defence Pact in 1969. Both nations shared a common enemy,

the Republic of Somalia.

The purpose of the pact was to enhance a joint military effort

in the region in the event of Somalia's attempt to invade any of

the two nations. To date the pact is still in existence.

THE SKIRMISHES

Consequent to the escalation of the tension between

Kenya and Somalia over NFD, the Kenya government mobilized her

forces in readiness for the envisaged skirmishes. Kenya had only

three infantry battalions (The 3rd Bn, the 5th Bn and the 1st Bn)

and one Support Regiment. In addition, there were also three

companies of para-military forces. Both the military and the

para-military forces were mobilized. The expectation of the

Somali regime was that upon the announcement of the constitution,

the Kenyan government would not include the NFD in its

constitutional arrangements.

The Kenya Regional Boundaries Commission which had been

formed in 1963 to verify and ratify regional boundaries had

included the NFD as part of Kenya forming the seventh province.

This matter was earlier discussed and agreed to at Lancaster

House in London by both Kenya and the British Colonialists

Office, prior to handing over self government to Kenya on the 1st

of June, 1963. The creation of the seventh province, under the

patronage of Kenya's new constitution was aimed at giving the

Somali people from the region greater freedom in the management

of their social and cultural affairs.

Kenya attained her independence on 12 December, 1963 with

the bilateral understanding that the matter would be resolved

amicably between the affected parties. Incidentally, no major

Click here to view image

decisions were effected other than a few insignificant Inter-

ministerial meetings, which yielded no permanent solution.

Eventually, it was left in suspense and to this day no explicit

solution has been mutually concluded by the affected parties. The

Kenyatta regime maintained that NFD was part of Kenya by all

legitimate rights and no further debate was encouraged.

Having deployed Forces in all four corners of the district

namely: Mandera, Garissa, Wajir, and Moyale, detachments were

further deployed at Malka-Mari, Bute, Buna, and Gurar. Their main

responsibility was to safeguard the Kenyan borders, maintain

peace and order, and thwart any effort by the militant

irredentist Somalis to incite the Kenyan Somalis to secede.

The campaign was divided into three distinct phases:

Phase I. 1963 - 1967. The main activity in this phase was

consistent with lethal skirmishes which inflicted serious

casualties and damage to the Kenyan troops in the region.

Along with these skirmishes was the intensification of

indoctrination and incitement of the Somalis against

the local Kenyan security forces. The Shifta fighters

operated in small groups of 20 to 100, divided into pockets

and raiding squads of 15 to 45. They engaged in ambushes,

mining activity, and destruction of equipment using

bazookas. After a vigorous joint effort by the Kenyan

military and the para-military forces, the Somali

Irredentist (Shifta) fighters were defeated. The shifta's

inherent problems, which contributed to Kenya's success, was

their long lines of communication aggravated by their

inability to resupply their fighting forces with ammunition

and arms. They were forced to withdraw back to Somalia in

order to reorganize, replenish, and regroup with a view to

striking again. The forward operational bases of the

Irredentist were Dolo, lugh Gonana, Baydhabo, and Baidoa.

Since there were no indicators of total peace in the area,

the Kenyan forces remained in position awaiting the possible

re-launching of the irredentist activity.

Phase II. 1967-1977: During this period the situation

was partially calm. There were very few skirmishes. However,

the irredentists continued to inflict casualties and losses

on the Kenya security forces. The Kenyan Defence Forces

seized this opportunity to recruit, train, and refit their

forces, to include formulating counter strategies.

Phase III: (The Ogaden War) General Siad Barre's

regime decided on a multi_strategic technic. He approached

the liberation of the Somali people using the strategy of

first securing the Ogaden and the Haud in Ethiopia and then

to switch forces southward into NFD. Ethiopia was busy, at

the time, fighting the Eritrean and Tigrean secessionists in

Northern Ethiopia. It was therefore relatively easy for the

Somali liberation forces to march to Jijiga, Dire Dawa, and

Harar with little or no resistance.

During this phase, the irredentists mounted precise, lethal,

accurate, and damaging attacks. The strategy was to maintain

contact with the Kenyan Defence Forces while preparing a major

offensive. The main activity was centered on mining roads and

ambushing Kenyan convoys.

Throughout the period covering the three phases, a

number of Somali-speaking officers and men defected from Kenya

Defence Forces to Somalia in of support of the Irredentist

movement and ideology. Incidentally, in the late 1980s and early

1990s Kenya started experiencing the phenomenon of the same

officers and men who had defected earlier now coming back. Well

over three quarter of those who defected have returned so far. A

majority of the defecters were interrogated and released to their

villages to start up life again as good citizens of Kenya.

THE CONFLICT

In the initial stages of the campaign, Kenya's young

government did not have the necessary infrastructure and manpower

to suppress the insurgency. They were not tactically prepared for

low intensity conflict. The command structure and particularly

the top military cadre was composed of the remnants of the

British officer corps, whose level of patriotism and commitment

to the conflict was below par. The immediate replacement of some

of the top command element improved the situation significantly.

The elderly and experienced platoon commanders who had

been elevated from warrant officer platoon commander

to fully-fledged officers led men into triumphant

battles against the scattered pro-secessionist fighting forces.

The major difficulties facing the Kenyan troops were centered on

lack of adequate and accurate intelligence, weather and terrain

constraints, and lack of adequate geographical knowledge about

the vast semi-arid NFD. The temperatures during the day were

sometimes unbearable and made it almost impossible to operate in.

During rainy seasons, road mobility almost brought road

transportation to a complete stand still. The unavailability of

updated maps, as well as the partial inability to read and

interpret them, added to the existing difficulties. Lack of local

support, insofar as intelligence and the lack of understanding of

the insurgents tactics, made the entire operation untenable and

excruciating. Kenyan forces experienced their hardest time ever

since the end of the Second World War.

The Somalis irredentist (Shifta) were more shrewd in

their tactics and approach throughout the period. They had the

advantage of local support from the people and the ability to

adapt to the environment. They had sufficient geographical

knowledge about the area and did not experience any problems with

the climate, since they all grew up in the same climatic areas.

Their convoy discipline and procedures were scrupulous

and impeccable. Convoys of logistic camels would move in tactical

waves. Wave number one would be composed of scouts, followed by

the deception party of a well armed squad,

then a small element as an early warning squad moving in column

of route, and finally the main body followed with armed guards on

the flanks. The basic composition of the convoys would be either

exclusively logistics or both logistics and families.

Any engagement would be met ferociously with the beating of

tins by the families while the main fighting elements were either

engaging from the rear or enveloping. All these activities were

concurrent and were intended to confuse the Kenyan forces into

committing troops wrongly or forcing them into total disarray

while the main force was moving away from the scene as fast as

possible. During extremely difficult situations, they would use

the rear guard to engage the Kenyan forces while their main force

was disengaging from the main battle ground. They never engaged

in decisive battles, but instead preferred to hit hard, inflict

heavy casualties, and retreat into thick bushes. Their main focus

of effort was the capture of heavy weapons, and the destruction

of trucks, as well as amoured fighting vehicles, using mainly

bazookas.

The Movement of logistics and families was confined to

evenings, moonlit nights, and pre-dawn hours. Based on their

intelligence, they had learned the habits of the Kenyan fighting

forces. Kenyan forces confined operational activities to 8.00 A.M

through 5.00 P.M in the afternoon. The Kenyan troops never

operated at night other than conducting limited ambush activities

at specific areas reported to be the main irredentist routes.

Click here to view image

In most cases, the ambushes were laid near bore holes where they

would bring their camels to drink water at night. This created

enormous problems for the Kenyan troops because there was no

distinct difference between the Shiftas and the indigenous people

from the region. However, this problem was eventually overcome

through liaison and coordination with loyal administrative

personnel from the region.

The main weapons carried by these secessionist forces were

the AK 47 rifle, the G3 Heckler and Koch, the AK 47 machine gun,

and bazookas. Other weapons were old Second World War rifles such

as the Mark 3 and Mark 4. The bazookas were mainly used to

immobilize the trucks while the machine guns were used for fire

suppression. At later stages in the campaign, they began using

three-fused, high explosive anti-tank mines made in Italy. There

were two different types of mines, one with three fuses, and the

other with four fuses. These mines were mainly obtained from the

Italians sympathizing with secession and from the Arab world. The

Somali irredentist fighters also obtained assault weapons from

Arab nations and Eastern European countries such as Hungary,

Bulgaria, and the Soviet Union.

The mines devastated the Kenyan transport assets, thus

forcing them to change the mode of operation from mounted troops

to cross country-foot operations. This had a tremendous drawback

on the overall fighting effectiveness, the motivation, and in the

general morale of the troops. The shortage of vehicles and

breakdowns, exacerbated by bad weather conditions,

together with the anti-tank mine dilemma made it almost

impossible for operations to be conducted deep in enemy areas.

The Somali irredentists would never attack without adequate

intelligence. Initial effort was geared to the gathering of

sufficient intelligence from sympathetic locals at least one week

in advance. The same locals were also used to carry out a

disinformation activity aimed at misleading the Kenyan forces

regarding their intentions and their disposition. Sometimes they

would use their agents to lead Kenyan forces into a pre-planned

ambush areas.

Occasionally, they planned raids in shopping centers to try

and obtain food for their troops. This development contributed to

another dimension of serious animosity between the secessionist

fighters and the local people who manifestly supported them.

Subsequently, support slowly shifted from total support of the

secessionist activity to supporting Kenyan troops. The

secessionist fighters would not break or steal from shops of

fellow Somalis but mainly the Boran and the Gurreh's shops. These

two communities were not considered as Somalis though the Gurrehs

spoke both languages, Boran and Somali.

THE OGADEN WAR

The changing of the guard in Somalia, after the

assassination of the Prime Minister, Dr Abdi Rashid Ali

Shermarke, saw Major General Siad Barre established in power.

This brought about a new dimensional approach to this regional

conflict. President Siad Barre adopted a more pragmatic approach

in contrast to the late Prime Minister who had been more flagrant

about supporting of the secessionist movement in both Ethiopia

and Kenya. Being a military professional, Gen Siad Barre decided

to approach the situation piece-meal. First and foremost, he made

friends with Kenya in an effort to paint a deceptive scenario

that there was no more secessionist ideology and that there would

be no more skirmishes. Essentially, this new image existed

practically only on paper. Limited, but lethal, skirmishes

continued with a serious impact on the Kenyan Defence Forces in

the NFD. Behind the scenes, President Siad Barre was planning a

strategy of forcefully securing the lost land and people in both

Kenya and Ethiopia, using military power. Thanks to his

increasingly close ties with the Soviet Union who enabled him

acquire substantial military arsernals.

In the meantime, Siad Barre regime continued to promote

insurgent movements in both Ethiopia and Kenya. He provided them

with both moral and material support. Following Ethiopian coup

which toppled Haile Selassie and brought Mengistus military

government to power, Somalia thought it an opportune time to

attempt to recover the lost territory as a phase towards total

recovery of all Somali inhabited territory. As a deception plan,

Siad Barre continued to seek a negotiated settlement of the

Ogaden and NFD disputes with the Mengistu and

Kenyatta regimes, while planning for a full scale offensive

operation to recover the territories. An organization calling

itself the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) had already

been formed. Along with this organization was another smaller

organization calling itself Somali-Abo Liberation Front (SALF).

Using these two liberation fronts, Siad Barre found it easy to

launch an offensive into Ogaden. He infiltrated his army into the

WSLF militia front and initiated the war. Negotiations were only

being used to buy time as a deception to ensure the Mengistu

regime would not pre-empt the offensive plans underway.

The first objective was the vast open grazing land between

the town of Jijiga and the undemarcated Southern boundary

between Ethiopia and Somalia. The offensive was fast and easy

since the only resistance was from a small element of police and

military personnel. By August, 1977 Somalia National Army had

captured all the ground inhabited by Somali-speaking people in

Ethiopia. Gen Siad Barre's strategy was to initiate negotiations

from a captured ground.

Subsequent to the ongoing events, Mengistu appealed to

Moscow for military assistance in form of equipment and technical

manpower. The Soviets responded massively with the Cubans in

support. 11,000 Cubans and 1500 Soviet advisers arrived in

Ethiopia. In response, Gen. Siad Barre expelled all the Soviets

from Somalia and repealed the friendship treaty with the USSR in

retaliation for the support given to Mengistu's regime.

Early February, 1978 the Soviet advisers, together with

Ethiopian forces, launched a counteroffensive. A two-staged

counterattack was launched from East and North, bypassing the dug

in Somali forces at Jijiga and attacking from the rear and the

flank with one force supporting the attack while the heavy tank

and helicopter gunships provided the main thrust. The Somalis

lost the war miserably simply because they did not have any

support from any other nation soon after they were abandoned by

the Soviets. The war end on March 9, 1978 with Somalia suffering

an overwhelming loss of equipment and defeat.

A third of the Somali army (over 8,000 men) had been lost in

the undeclared war. Three quarters of the Somalia's mechanized

and tank force had been lost in the war. Nearly a half of the

aircraft were destroyed or were non-operational due to lack of

spare parts after the severing of the relationship with the

Soviet Union. Nevertheless, the Western Somali Liberation Front

and Somali-Abo Liberation Front resumed their guerilla activities

in the region despite the disastrous loss of the Ogaden war. The

Ogaden war was to mark the beginning of a major offensive

campaign into Kenya to secure the NFD and the Somali speaking

people. Notably, there were other phases aimed at recovering the

land and the Somali speaking people in the Former French

Somaliland (Now Djibouti). However, this plan had to be abandoned

indefinitely following the Ogaden war disaster.

Ironically, Gen Siad Barre's initial strategy to use military

force secure the Haud and Ogaden during phase I, and then the NFD

as phase II became explicitly infeasible. The dramatic twist of

events which culminated in an awesome defeat of the Somali troops

left the Siad Barre regime in total disarray. The morale of the

troops plummeted especially with the massive losses. It would

take Somalia many years of recuperating before it could revisit

the issue again. The war had a serious negative impact on the

Somalia's socio-political and economic status.

LESSONS LEARNED

The Kenyan Defence Forces learned several lessons

following the conflict with the Somali Irredentist fighters. The

following is an elaborated outline of the lessons learned:

- Knowledgeability: The Kenyan Forces did not have adequate

knowledge about the people they were fighting. They did not

understand the enemy's habits, culture, and traditions. They were

operating in a completely strange territory. Also, the Kenyan

Forces did not have adequate terrain and geographic information

about the area. They were fighting an enemy on its own terrain.

The need to have substantial socio-economic knowledge about the

enemy and the terrain is very important in any warfare and more

emphatically low imtensity conflict.

-Intelligence: Lack of local support made it extremely

difficult for the Kenyan Forces to operate in the area. There was

complete lack of intelligence on enemy activity, enemy order of

battle, and enemy disposition. Human intelligence proved counter

productive because most of the sources were compromised agents of

the enemy or double-dealing opportunist informers. They proved

totally unreliable. The Kenyan Defence Forces ended up developing

their own collection assets including employing the same agents

on disinformation activities intended to mislead and to enhance

deception. The need to have adequate intelligence about the enemy

prior to initiating any operational activity is of paramount

importance.

Tactics and Logistics: Low intensity conflict was a new form

of warfare to the Kenyan Forces. Therefore it was extremely

difficult in the initial stages for the Kenyan Forces to cope

with the situation. The terrain and weather constraints worsened

the situation. Logistic sustainability and survivability in an

area where road communication was rare, created another big

problem. The Kenyan Forces could not live off the land since the

local populace were hostile. There were no lines of communication

for resupply of the food to the jungle camps and worse still

there were no helicopters to heli-drop the supplies. The only

option was to use human and animal transport to carry ammunition

and food to the camps. Logistics is war and war is logistics.

Without logistics, tactics and strategy will have little impact

on the success of any operation. Above all is mobility. Without

mobility to facilitate transportation of logistics and manpower

resources in battle is futile.

Training: The troops were not exposed to low intensity

conflict warfare; therefore additional training was required to

get them to fight effectively in the jungle. There is always a

need to train hard on all types of warfare in peacetime to be

able to fight easily in times of war. The Kenyan military focus

of training at that time was conventional tactics mainly and very

little training on unconventional ones.

Strategy: There was no overriding strategy to counter the

low intensity conflict warfare since it was new to the Kenyan

Forces. The Kenyan approach was conventional while the insurgent

was unconventional using hit and run strategy. Attack

unexpectedly from uexpected direction and time; inflict heavy

casualty and diasppear into the thin air. Speed and accuracy is

the key factor in this circumstance. It is important to formulate

strategy prior to undertaking any complex maneuver such as low

intensity conflict. This can only be achieved by learning and

analyzing the enemy's habits and methodology of conducting

operations in order to formulate a counter strategy.

CONCLUSION

Late 1975 through to 1978/79, the situation in Kenya had

improved drastically. The level of skirmishes had diminished

considerably, though there were minor clashes with Somali

National Army logistic convoys withdrawing from the war front in

Ethiopia.

Following this trend, Kenyan troops remained in their respective

locations keeping watch as usual. Their intelligence techniques

which included interrogation to establish the shifta future plans

had improved with time. The resettlement of the local population

and control mechanisms had also achieved a great deal of success.

On the socio-economic and political dimension, Kenya

was developing rapidly, given the worthwhile leadership of

the late Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and the current President Daniel

Toroitich Arap Moi. The socio-economic infrastructure had greatly

improved in the NFD. Unlike the colonial era, the Somali

community in the region were enjoying equal treatment and

opportunities like everybody else everywhere in Kenya. The old

mentality of secession had diminished from the minds of the

Somali-speaking people of NFD. The government of Kenya had

carried out a carefully tailored psychological, social, and

economic pacification program focused on the daily human domestic

necessities and amenities such as food, hospitals, schools,

communications, and electricity.

By contrast, the socio-political and economic situation

in Somalia had taken a nose dive following the aftermath of the

Ogaden War. The Kenyan Somalis were enjoying the greatest

privileges compared to fellow Somalis in Somalia. It reached a

culminating point where they openly conceded that they were not

interested in seceding to join Somalia or becoming part of

Somalia whatsoever. They were politically, economically, and

sociologically enjoying the same status as everybody else unlike

during the past era when they were segregated and treated like

aliens. The issue regarding secession is now treated negatively

whenever it is discussed in public. Such discussions would not be

entertained by the majority of the Kenyan Somali people in the

country and particularly in the NFD.

The disintegration of the socio-political and economic

situation in Somalia added up to this positive demonstration.

Over the period between 1980 and 1990, there has been an isolated

element of armed bandits still existing in the area.

Additionally, there has also been a lot of hungry renegade Somali

army soldiers crossing into Kenya in search of greener pastures

for survival. This has required the Kenya government authorities

continue deploying troops in the area in order to insure

tranquility prevailed and that people are able to go about their

business peacefully.

The improvement of fighting skills and abundant

sophisticated fighting resources has enabled the Kenyan Forces to

effectively combat the secessionists. On the other hand, lack of

local support has further made it extremely difficult for the

secessionist remnants to sustain or live off the land as was the

case in the early 1960 and 1970. These days, anybody in

possession of a weapon or acting strangely would be reported

swiftly to the administration or arrested and handed over to the

security forces by the loyal population.

The greater Somali concept of the unification of all Somalis

still exists. The five point star in the Somali national flag

representing the five Somali inhabited regions consisting of

former British Somaliland, the former Italian Somaliland, the

NFD, the Ogaden, and Djibouti has not been changed. Moreover,

Somalia has not publicly renounced her claim over the frontier in

the Horn of Africa. These frontiers constitute a total area of

374,200 square miles.

As provided in the United Nations charter,

Somalia is a distinct nation entitled to a separate existence and

to rights and duties similar to those of other nations in the

world. This statement presupposes that the idealogy of the

unification of the entire Somali community remains firm and

unresolved to date. The Colonial scramble to dominate and

influence in the Horn of Africa involved three countries namely

British, Italy and France. The aftermath of this scramble is what

we see presently as boundary disputes in the region. It is the

root cause of these problems.

African frontier problems such as this particular case are

a product inherited from colonial days. The colonialist

artificially demarcated frontiers without regard to tribal

alignments. They displayed no respect for ethnic, cultural and

socio-economic background of the indigenous people.

The future of this legend remains in the hands of our

leaders and the people of the land. The continuing peace in the

region will undoubtedly guarantee lasting socio-economic

development and stability. An Improved situation in Somalia will

further increase the assurance of peace since many have learned

from the past and would not endeavor to venture into unnecessary

warlike activities which would result in the massive loss of life

and property.

Lastly, the three countries namely, Kenya, Ethiopia, and

Djibouti, should strive to resolve this issue through arbitration

by both the Organization of African Unity and United Nation

Organization.